Last week I shared an episode about income, and how A.I. (if it works the way techbros say it will and we get to AGI and our machines can do most everything we can do) will end up functionally destroying our current economic loop.

I called this episode “Who buys your stuff, robots?” and, well… it caught fire on YouTube.

I posted it last Tuesday and went to bed that night with 91 YouTube subscribers (I remember, because I thought: “I wonder when I’ll get to 100?”) and woke up to 50 new subscribers and 1000 views on the video. And it turned out it was just getting started.

When I hit publish on this article, last week’s episode had 26,000+ views, 800+ comments and 1800+ likes. I’m blown away, and SO delighted it’s resonating. If you haven’t yet checked out the YouTube channel and you’d like to, click right here.

OK, last week I also promised to tell you about something that blew my mind a bit, so let’s get into it.

Today I’m going to take you on a bit of a “thrill ride” that concerns one of the LEAST thrilling or sexy things I can think of: DEBT.

I know that might sound completely ridiculous, but I did not anticipate the mind-bending adventure this topic would take me on, and I’d like to take you on that journey now!

The Question That Wouldn’t Let Me Go

Here’s what happened…

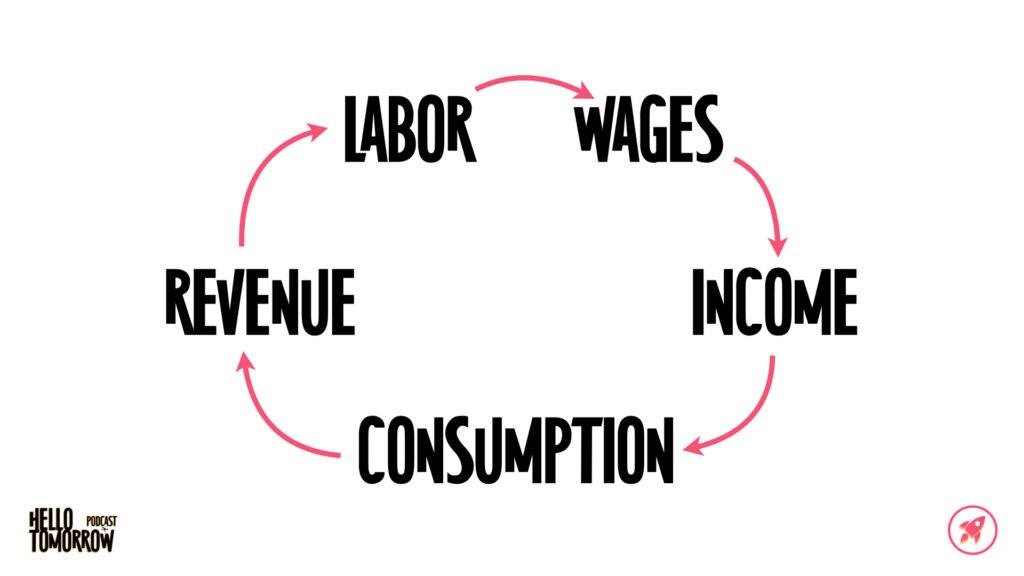

Last time we talked about The Loop That Holds Up The World, and I showed you a diagram, a simple loop: Labor to Wages to Income to Consumption to Revenue and back to Labor.

When I made it, I used the word INCOME for simplicity.

But right before I posted the last episode, I realized “income” isn’t EXACTLY what I meant. Income is everything you bring IN.

What I really mean to be right there is “what’s left over after you’ve paid your bills.”

That’s what we ought to use to buy things, right?

What do we call THAT?

I thought for a moment and realized I didn’t know the answer to this question. I was a bit blindsided — both by the not-knowing AND by the realization that I’d never really thought about this before.

Basically, the question is: what do we call profit for individuals or families?

You know what I mean? Profit is what’s left over after you’ve paid your expenses in a company. But what do you call that same money when you’ve paid all your expenses at home?

Savings? No, that implies that it’s sitting in a bank.

Disposable income? That’s actually a specific term, used for what’s left after taxes, not expenses.

Margin? Feels even more business-y than “profit.”

Emergency fund? Feels like money for savings, not for “spendings.”

Discretionary income? Better, I think, but has a connotation of frivolity to it.

Surplus? This might be the most accurate word — but when’s the last time you heard someone say, “Yup, we’ve got some household surplus this month!”?

Yeah, me neither.

As I went through this list, something clicked:

Isn’t it strange that we ALL understand exactly what “profit” is — but we don’t even have a WORD for its equivalent in our personal lives?

The Power Of Language

I’ve always been obsessed with language.

I love great lyrics and clever wordplay. I’ve enjoyed reading and writing ever since I could do either of these things.

But if memory serves, what really unleashed a new depth on the topic of language was a book I read in college called Metaphors We Live By. I’d never considered how metaphors shape our thinking. Since then, I’ve come to believe a few truths about language:

1. Language is formative — we think in language, so this means if we change the words we use we can change the way we think

2. Language indicates our worldview — the words we use “give away” our capacity for the world we are able to presently see

3. Language always has a framing power — the words you choose to use to a large degree dictate what other people will be looking at when they hear your language

Last week, I added another insight to my list…

Language indicates what matters — we give words to things we care about.

Businesses have profit.

Investors have returns.

Families have… nothing?

Feels about right…

But honestly. That leftover money — the surplus — is what actually fuels the consumption part of the economy. Without it, The Loop fails!

And we don’t have a word for it.

How is it possible that we don’t have a word for such an important part of The Loop?

The answer reveals the most important dividing line in capitalism… one we’re taught not to see.

The Real Divide: Labor and Capital

Inside capitalism, there are two basic roles: Labor and Capital.

If you are Labor, you sell your time and energy via work. You get paid after your work is done.

If you are Capital, you own assets. Your assets make more money.

And here’s the quiet rule built into the system that we don’t talk about:

If you are Labor, surplus is… a problem. Surplus gives you breathing room. Breathing room gives you choice. Choice gives you leverage.

So… well… the system doesn’t really want you to have those things.

Why? As always: because it doesn’t make more capital! So, personal surplus is squeezed down to as close to nothing as possible.

But if you are Capital?

Surplus is the point. It actually has a LOT of language over there: profit, returns, yield, appreciation.

Same economy.

Two completely different relationships to surplus.

If You Had Surplus You Wouldn’t Need Debt

OK, I know I promised you some sultry pillow talk about DEBT, and now we’re ready to go there.

Because the real baller Capitalist move isn’t just reducing personal surplus.

It’s eliminating surplus so completely that you need something else to cover your basic needs.

What is that thing?

You guessed it: debt.

I’m not talking about “luxuries,” my friends. I’m just talking about LIFE.

Housing. Healthcare. Education. Transportation. Emergencies.

Can you pay for ANY of these without debt?

Did you buy your house without debt? If something unexpected happens, can you cover the medical bills? Could you pay for college in cash? How about your car; did you pay for that outright? And you’ve got a stash of gold for your emergency fund, right?

Do you see it??

When surplus disappears, debt stops being optional and starts being necessary.

And that’s the point.

It’s not a conspiracy, it’s just “good capitalism!” Because if you rely on debt to live, you are permanently tied to future work.

You can’t pause.

You can’t refuse.

You can’t walk away.

Debt replaces surplus as the buffer.

Credit replaces savings as the safety net.

And the system no longer needs to pay you enough to live — it just needs to make sure you can borrow the difference.

That’s not a wage failure.

That’s a design feature.

This is what we’re told to be grateful for.

Debt Is Not “Borrowing Money”

There’s one more layer of mind-bending here… you ready?

What IS debt??

Ask me this question two weeks ago, and I would’ve said I understand debt pretty darn well.

I’ve got student loans, I’ve bought and sold houses, built companies with lines of credit, raised money, filed bankruptcy… I’ve got a pretty solid understanding of what debt is, thankyouverymuch.

But… I didn’t really get it.

I mentioned this briefly in last week’s episode, when we talked about capitalism not being a “growth system” but a system that FEEDS ON GROWTH.

Capitalism requires continuous growth because it borrows from the future to function in the present… and the future has to keep getting bigger to cover the tab. And continual growth can only happen when there’s something continual to extract, the 5 most common things being: labor, energy, land, attention, and debt.

I think it’s relatively straightforward to see how capitalism extracts from the first four…

Labor — yeah… you get this one, intimately; almost all of us feel this every damn day because we’re the labor being extracted from

Energy — we literally extract resources out of the earth and burn them to power all our stuff

Land — when we want a piece of land we displace any other species on it… you’ve seen humans do this, right?

Attention — we will endless scroll, doomscroll, micro-dopamine-hit ourselves to death

But what about debt?

What does extraction have to do with debt?

Well, this is where we all become futurists.

Debt, my friends, is extraction of your FUTURE labor.

Debt is simply a claim on labor that you will labor in the future.

When you take on debt, you’re not spending what you have, you’re committing time you haven’t lived yet.

Future hours.

Future energy.

Future attention.

Oh, and with interest!

Credit cards aren’t just “convenience.” Mortgages aren’t just about the “American Dream.” These things are THE way “good capitalism” keeps consumption going even when surplus is long gone.

And this… isn’t new.

It Could Be A Wonderful Life

For most of human history, debt was local and relational. Neighbors owed neighbors. Merchants extended trust. Debt was visible, human-scale, bounded by relationship.

When credit works like that, there are natural limits. People don’t extract endlessly from people they have to see every day. Reputation matters. Community matters. And for most of human history, debt was temporary.

You borrowed for a season.

For a bad harvest.

For a specific need.

And then — this is critically important — the debt ended.

Debt had a beginning and an end, and most people expected to live large parts of their lives not owing anyone anything.

But that kind of system doesn’t scale.

By the early 1900s, mortgages started lengthening. By the 1930s, 30-year mortgages became the new normal. Not short loans. Not emergency credit.

Decades-long commitments.

For the first time, at scale, people weren’t just borrowing to get through a rough patch, they were borrowing in a way that shaped their entire adult life.

Homes weren’t being bought with money people had already saved, they were being bought with thirty years of promised work.

From that moment on, the economy wasn’t just built on what existed today, it was built on the assumption that people would keep showing up to work, without interruption, for decades.

This is where George Bailey comes in.

If you’ve ever seen It’s A Wonderful Life, you probably remember the bank run scene, with George pleading to everyone to understand something vitally important about their money.

Let’s listen to Jimmy Stewart do it, of course:

He goes on, convinces the town to band together, and uses the money he was going to spend on his honeymoon to float everyone in the near-term.

That scene is showing us what the world used to be… and could become again.

George is trying to hold onto a form of credit that was already disappearing. He’s trying to keep debt human in a world that’s learned how to make it abstract.

That’s why the scene feels so emotional.

We’re not watching a normal banker, we’re watching a man fighting the tide of capital.

To us today, George Bailey represents the road not taken: a system where credit stayed relational, limited, and accountable to its community.

The villain of the movie is, of course, Mr. Potter, who represents a financial system where debt is detached from people, scaled up, and optimized for extraction.

That’s why this movie lands, 80 years later. (Yes, seriously; it came out in 1946.)

We recognize instantly that once debt is no longer personal, it becomes… something else. Something extractive and dark. Once debt stretches across decades, it stops being a tool you use occasionally and starts becoming the condition you live inside.

When debt becomes this kind of monster, the question changes from:

“Can I pay this back?”

To:

“Can I keep working long enough to survive this?”

That’s a completely different relationship to debt. And it changes our behavior. We can’t walk away, we can’t pause, we can’t stop running, because our future income is already spoken for.

This is why we so badly need a new organizing story.

It still COULD be a wonderful life… but we will need new beliefs and new structures to make this possible.

The Debt Pattern Is Everywhere

If this is starting to feel familiar, that’s not an accident.

Once you see how debt really works — how it pulls value from the future to keep the present moving — you start seeing the same pattern in other places too.

For example, we see it in technology right now with a possible A.I. investment bubble. Entire companies and industries are being valued not on what exists today, but on what the future is expected to deliver. Productivity gains that haven’t materialized yet. Profits that don’t yet exist.

It’s the same move.

When growth runs out of real things to extract in the present, it turns to the future.

In finance, we call that debt.

In tech, we call it investment.

In real estate, we call it a mortgage.

In everyday life, we call it credit cards.

Different arenas.

Same logic.

It’s all about pulling from tomorrow to keep today going.

And once you recognize that pattern, it becomes hard to unsee, because it’s not an exception.

It’s how the system keeps functioning.

Why Life Feels So Heavy

If this feels heavy or familiar, it’s because you already felt it in your body.

Like me, you maybe just didn’t have the language.

You know, and I know:

- We can’t quit

- We can’t pause

- We can’t miss a paycheck

- We can’t risk instability

That constant background noise? That continual underlying stress? That sense that one wrong move could unravel everything?

That’s not personal failure.

It’s what it feels like to live in a system where surplus has been systematically removed from your field of possibilities and debt has taken its place.

Of course life feels heavy.

The Optimistic Rebellion

The optimistic rebellion this week is important. It’s not fixing yourself. And it’s not — not quite yet — taking on the system. We’ll get there, but today…

Today the rebellion is giving yourself grace.

You are not doing this wrong. You didn’t choose this pressure. You didn’t design this system. The system chose these conditions for you.

So this week, your assignment as a rebel is to take an extra breath.

And when the stress shows up, remind yourself: this kind of pressure was never meant to be carried alone. Reach out to someone. Share this episode as a conversation starter. Get coffee with a friend. Share the weight. Help each other.

Clarity is the first form of freedom.

And once we see the system clearly, we can’t unsee it.

So take the breath. Give yourself grace.

And then — when you’re ready — start asking out loud: “Why do I have to borrow against my future just to live in the present?”

When enough of us start asking that question, we’ll be able to change the system.